The Dutch Are WEIRD, and So Is ChatGPT

I’m Dutch, and whenever I’m abroad, people figure this out pretty quickly. It’s usually the bluntness. We tend to be direct, to the point, and question things constantly. To a lot of people, this comes across as… well, weird.

That word, “weird”, has been on my mind a lot lately, especially when I hear the LLM providers tell us that Large Language Models (LLMs) have achieved “human-level performance.” I’ve been in tech and security for a long time, and I’ve seen more “revolutions” than I can count, but the chatter about this one is everywhere. Each model is more human then the last one it seems.

It’s an impressive claim, and the demos are slick. But in our line of work, we’re paid to be paranoid. We’re trained to ask the follow-up questions, the ones that spoil the party. When I hear “human-level performance,” one question comes to mind: “Which humans?”

It’s not a trick question. We’re a weirdly diverse species. A rice farmer in rural China, a herder in the Maasai Mara, and a philosophy student in Stockholm don’t just have different opinions; their brains are wired to process information in fundamentally different ways. Trust, morality, logic, even how they see themselves… it’s all variable.

The problem is, these LLMs aren’t being trained on that full spectrum of diversity. They’re being trained on data from one very specific, and globally unusual, sliver of humanity. That sliver is what researchers call WEIRD: Western, (sidenote: Even though some politicians think it a good idea to destroy our educational system) , Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic.

If you’re reading this, you are almost certainly part of that group. And so, it turns out, is ChatGPT.

The “WEIRD in, WEIRD out” problem

In security, we have a foundational concept: “Garbage In, Garbage Out.” A system is only as good as the data you feed it. A model trained on junk will give you junk. AI is no different.

So, how did our supposedly “global” AI models end up with one very specific psychological profile? They were trained on the internet. And the internet is not a mirror of humanity; it’s a funhouse mirror that reflects its most active users.

Access: Nearly half the world’s population isn’t even online. The data we’re scraping is missing billions of perspectives from the start. That’s not a rounding error; it’s a colossal blind spot.

Language: The training data is overwhelmingly, colossally dominated by English. This isn’t just a language issue; it’s a cultural one. English-speaking populations are, by definition, a psychological outlier on the global stage.

The AI, in its quest to find patterns, is just learning the patterns of its most over-represented users. It’s not just “Garbage In, Garbage Out.” It’s “WEIRD In, WEIRD Out.” The model is faithfully replicating the psychological skew of its training data.

The evidence: how to build a digital Dutchman

The researchers didn’t just guess this; they tested it. They gave ChatGPT a battery of classic cross-cultural psychology tests and compared its answers to a massive dataset from 65 nations. The results are quite astounding.

Test 1: The “Cultural Map” First, they used the World Values Survey—a huge dataset on global attitudes about morality, politics, and trust. They mapped all 65 nations and ChatGPT to see who “clustered” with whom.

ChatGPT didn’t land in some neutral “robot space.” It landed smack in the middle of the WEIRD cluster. Its closest psychological neighbors? The United States, Canada, Great Britain, Australia… and, of course, The Netherlands.

The correlation was stark: the less WEIRD a country’s culture was, the less its people’s values resembled ChatGPT’s.

Test 2: The “Shampoo, Hair, Beard” Test This is the one that really got me. In a classic “triad task,” you’re given three words and asked to pair the two that are most related. For example: “shampoo,” “hair,” and “beard.”

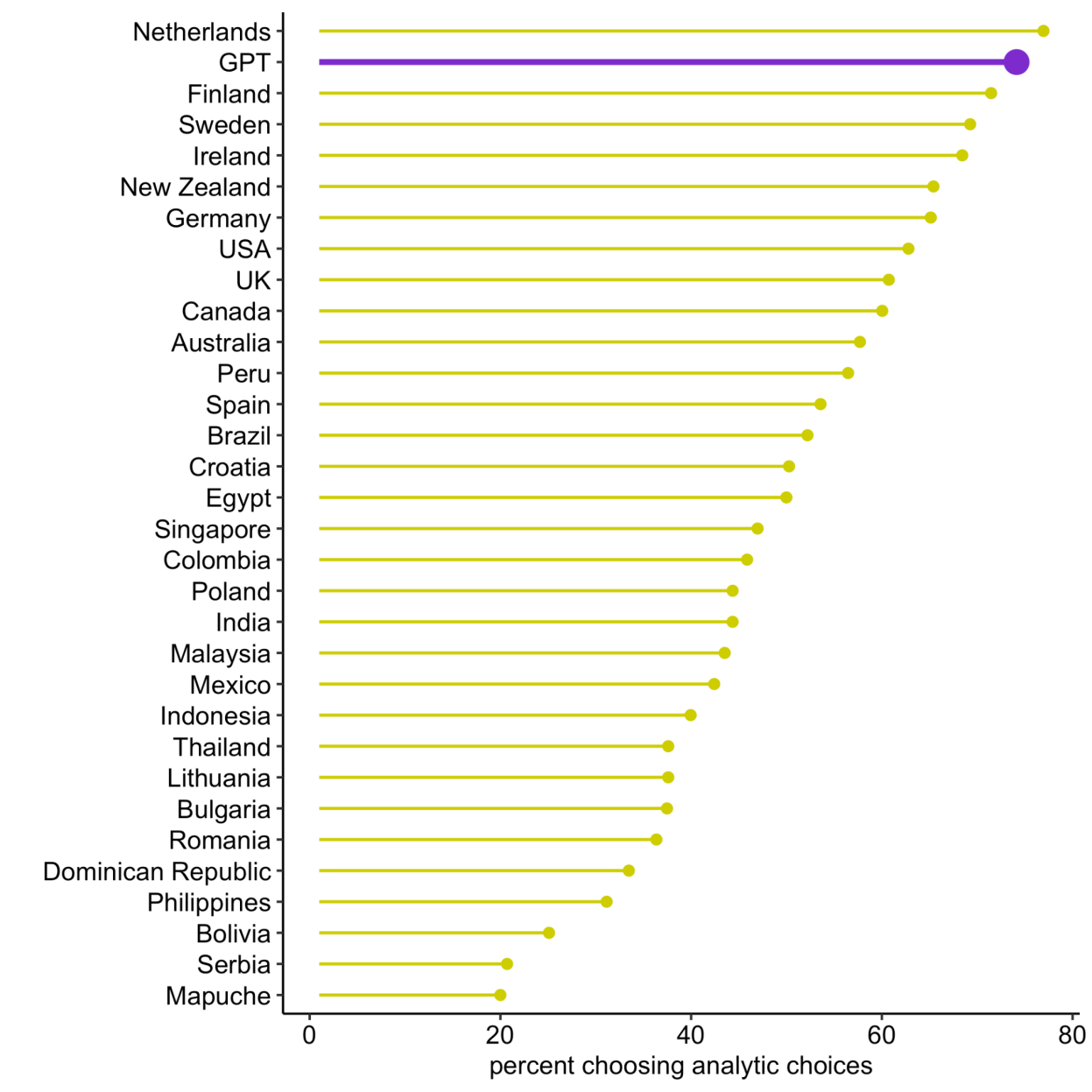

The difference in thinking is stark. A holistic thinker, common in less-WEIRD societies, tends to pair “shampoo” and “hair” because they have a functional relationship (you use one on the other). In contrast, an analytic thinker, common in WEIRD societies, pairs “hair” and “beard” because they belong to the same abstract category (they are both types of hair).

When they ran this test on GPT 1,100 times, the results were stunning. On the graph of all human populations, GPT’s percentage of analytic, WEIRD-style choices was almost identical to that of the Netherlands. They are plotted as next-door neighbors at the very top of the analytic-thinking chart.

It doesn’t just agree with the Dutch; it thinks like them.

Test 3: The “Who Am I?” Test This bias isn’t just about values or logic; it’s about a fundamental sense of self. Psychologists have a simple test: ask someone to complete the sentence “I am…” ten times.

The responses to this test show a clear cultural divide. WEIRD people overwhelmingly list personal attributes: “I am smart,” “I am an athlete,” “I am hardworking.” In sharp contrast, people from less-WEIRD cultures overwhelmingly list social roles and relationships: “I am a son,” “I am a member of my village,” “I am an employee of X company.”

So, what does ChatGPT think an “average person” is? You guessed it. When asked, it generated a list of personal characteristics, mirroring the self-concept of US undergrads. It perceives the “average human” through a WEIRD lens, completely missing the relational self-concept that is the norm for most of the planet.

Why this matters

Okay, so the AI is a bit weird. Why should we, as tech professionals, care? Because in our field, a system with a built-in, predictable blind spot isn’t a curiosity, it’s a liability.

We’re in the business of risk. We are rushing to integrate these models into every layer of our stack. They’re not just toys anymore. They’re in our code review pipelines, our content moderation filters, and our HR software that screens resumes.

Now, picture that “Digital Dutchman” logic applied at scale. A content moderation filter trained on WEIRD norms of “harm” will be systematically blind to what’s considered offensive or dangerous in other cultures, while over-policing things it finds “bizarre.” An HR tool built on WEIRD ideas of self-promotion (“I am smart”) might filter out perfectly qualified candidates from cultures where boasting is a taboo and group-contribution is the norm (“We achieved…”). And a code-assist AI, when asked for “simple” or “logical” code, will default to an analytic, WEIRD-style structure. Is that always the right, most robust, or most secure solution? Or just the one that feels right to its internal psychologist?

This isn’t a hypothetical problem. The researchers noted this bias persists even in multilingual models [1]. You can’t just “translate” your way out of a core psychological skew. What we have here is a systemic vulnerability.

We didn’t build a “Human” AI, we built a WEIRD one.

The takeaway here isn’t that LLMs are useless. It’s that we have to be ruthlessly realistic about what they are. This isn’t a step toward “artificial general intelligence.” This is an echo chamber.

These models aren’t “human-like.” They are a-human-like. They’re stochastic parrots that have been trained on a very specific, psychologically peculiar dataset.

A tool that is fundamentally blind to the perspectives of most of the planet isn’t “objective.” It’s a system with a massive, built-in bias. And as we race to embed this system into the foundations of our global society, we’re not building a universal brain; we’re exporting a single, peculiar psychology.

And for those of us in the security field, a system with a blind spot that big… well, that’s what we call job security.

Find more Research Driven Blogs .

Bibliography

- Atari, M., Xue, M. J., Park, P. S., Blasi, D. E., & Henrich, J. (2023). Which Humans? (Unpublished manuscript). Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University.